At my high school, piano was a required “class”, and therefore, piano practices were something scheduled during the regular school day. I believed this to be a serious advantage because I no longer had to figure out a time to schedule practice between all the homework and extra-curricular activities that were beginning to fill my after-school hours.

The piano practices were held in the basement of our school building. Six to seven rooms were in the area with a piano in each, and a monitor would sit in the main area, strolling around and peering through the window into each practice room at regular intervals to make sure that students were, indeed, playing the piano and not reading books or doing other homework during this 40 minute period. (This was before cell phones, so you can only imagine the distractions that must take place now!)

I had taken piano for 9 years prior to entering high school, and so I knew how to structure my piano practices in a way that allowed me to make progress because my previous teacher had taught me how. I had some friends, however, who were taking piano lessons for their first time and had no idea how to practice in this context — a timed setting with a lot of freedom. Through the wall of the practice room next to me, I could hear a first-year piano student playing through a few fundamental pieces he was working on over and over, as fast as he could, for a few minutes. And then proceeding to spend the next 35 minutes by playing “Heart and Soul” or “Chopsticks” on repeat, or sometimes just banging around on the keys. Obviously 40 minutes was much too long to work on a few short, basic pieces for this beginning level student. It was a waste of his time to be in this room, arbitrarily filling the minutes. I’m not sure how “rewarding” he felt this 40 minute practice session was, and he looked a bit glazed over when he emerged from the room at the end of the period.

I’ve blogged before about how “timed goals” aren’t necessarily a great setup for practicing, but today I want to get really specific about setting up a practice plan for your student. This is going to sound very….calculated at first. But it need not always be this way. Through this charting you’ll be teaching your child HOW to practice, and then she will eventually reach the point where this is not necessary because she understands how to practice without much oversight.

Know this: your child needs your help to learn how to practice in order to ensure progression. As your child begins to feel confident and accomplished, she will be able to structure her practices more independently.

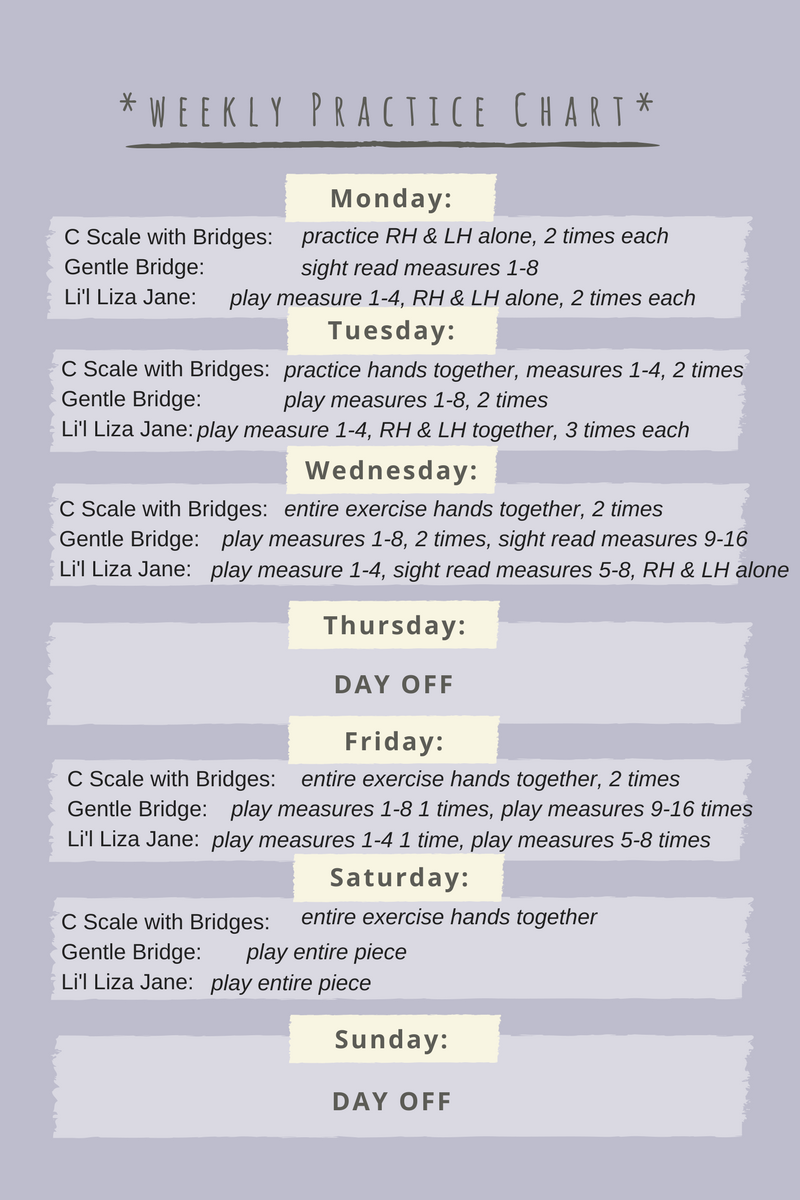

I like to show and tell, so here’s an example of what a practice chart might look like for the assignments in my Level 2 Lesson #1 in my Busy Kids Do Piano Program:

This particular lesson includes a technique exercise and 2 pieces. You’ll notice I’ve broken down these pieces into small sections and set daily goals. When my student finishes working her way through these specific assignments, her practice session is finished. Likely her practice will be a little longer on Monday. By Saturday, she might just breeze through the assignment very quickly — a reward in and of itself for all her work during the week!

This may seem excessive or time-consuming, but just spending a few extra minutes each week to help your student get really clear on her practicing goals will help SO MUCH when it comes to progress, frustration, tolerance and confidence. And that pay-off is so worth those few extra minutes.

2 thoughts on “Making A Practice Plan.”